How to Write User Stories

Author: Becky Taylor;

Reading Time: 10 minutes

We've made this resource open. You are free to copy and adapt it. Read the terms.

If you would like more help with your digital challenge, book a free session with DigiCymru.

Over the last 10 years user stories have become an integral part of the research and design process I follow. They help organisations to be user-centered and meet their users’ objectives.

User stories are simple statements that focus on what the user wants to achieve. They define the audience/situation, motivation and expectation that a person has, associated with a service or product. They’re brilliant because they help you to understand a user’s specific context, need and goal in one statement. Most importantly, user stories enable you to directly link user needs to solutions that you can design or build.

If you’ve just spent time better understanding your audience and have used that information to write a set of user stories, I imagine you’re now raring to get started and make some progress.

Maybe you’re thinking you just need to start designing some ideas and solutions? But you’re not quite sure how to get started, or if this is even the right thing to do. Budget and resources are tight, and you’ve got a lot to achieve. So, the pressure is on to take action, yet make the most impact with your time, energy and money.

User stories should be actionable.

Once you have a user story which expresses a particular need, you should be able to prioritise that story and assign it as a task to a member of your team. A set of user stories leads to the completion of projects with a specific scope. You should be able to say “XXX and YYY allow us to complete this story” and by doing so, know that you have answered a user’s need with your website or service.

But user stories are only actionable if they’re written in the right way.

I’ve seen hours and days wasted because teams are confused on what they’re supposed to be working on – the user stories weren’t clear enough, or they were so big it was impossible to even estimate how much time it would take to design a solution.

Imagine you have a set of user stories that you feel really clear on. You know what they are, why they’re needed and you’ll know exactly when you’ve completed them.

This means you can accurately manage time, resources and budget, and make sure you hit those objectives, for both your users and your organisation.

The great thing is that it’s not hard to get to this point. This article is going to give you some simple steps to do exactly that, so with no more than a few hours investment, you’ll be ready to get started on making improvements to your digital and service experience.

How do you check that your user stories are actionable?

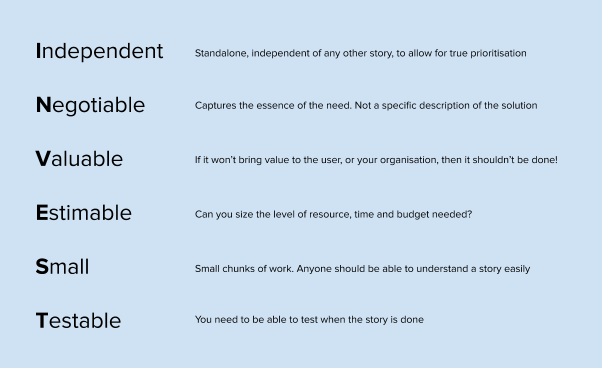

I use a framework called INVEST to do this.

This framework was originally created by Bill Wake and is a way to ensure you write stories with the right characteristics to ensure they’re actionable and measurable. Otherwise, how are you going to know what to do with them? How will you know how to prioritise them? Finally, how will you know when they’re done?

Ideally, you’d have INVEST in mind at the time of writing your stories, but it’s just as easy to review your stories too. So, let’s unpack what INVEST means.

Independent

A user story should be standalone, independent of any other story, to allow for true prioritisation. This means you can implement or schedule the story in any order, to suit a user’s needs or your organisations’ resources.

In reality, this isn’t always possible, so if you have two other stories that tightly relate to another story, consider merging them into one story.

Negotiable

A story should capture the essence of the need that must be met, yet not be overly definitive about how it should be solved. A story is not an explicit list of details and features that are set in stone. The point of a user story is to ensure you meet a user need, but the specific details of how you solve it may not be defined or known yet, and aren’t always needed in order to prioritise stories. Most stories are likely to require collaboration with different members of your team, e.g. those that know the user, those that are going to build the final solution or those that prioritise the work that you do, to provide clarity on how you might solve it. Your story needs to be open enough to enable this collaboration, and to let everyone feed in ideas.

Valuable

If a story isn’t going to bring value to the user, or your organisation, then it shouldn’t be done! Remember the whole point of a user story is to ensure what you do is user-centered. So when looking at your stories, if completing it seems more valuable to the management or to the development team, than the user, you need to question the true value of the story and whether it is something you should be doing.

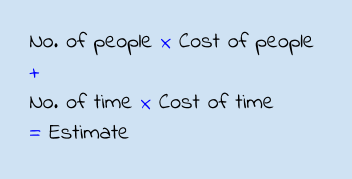

Estimable

You should be able to look at a user story and size the level of resource, time and budget needed, so that you know what work is involved to solve the user’s problem, and be able to prioritise it. If you don’t know how long it will take to address the user’s problem, or what resources are needed, how will you know if you can schedule it or accomplish the task? It doesn’t have to be exact, but enough to rank and schedule it. This links to how negotiable and small it is…if you don’t have enough information to understand the story, or it is so big you can’t fathom it, you’re not going to be able to estimate it.

Being able to estimate also depends on the experience of your team and the story itself. For example, if it’s a very technical story and you don’t have a technical web developer to hand, you will struggle to estimate it. In this case, you could set aside constrained amounts of time per story to look into the details of what it could take to implement it. That way, you can work it out, but not waste time.

Small

Stories are small chunks of work and anyone should be able to understand a story easily. There are two meanings to ‘small’ here. First off, stories are small chunks of work. We’re talking days or at most weeks, not months. Any bigger and the task should be broken down into smaller, independent stories, because otherwise you can’t estimate them. User stories come from the ‘agile’ way of thinking, where the focus is on always delivering value, and doing the simplest thing that works, then stopping! You might be able to meet a user need through an elaborate and complex solution, but if you can meet the need adequately through a solution half as complex, do that.

Secondly, keep the actual writing of the user story small – it should be easy for anyone to understand at first-read. Remember, it’s about capturing the essence, which can be elaborated on later, through further discussion or collaboration.

Testable

You need to be able to test when the story is done. Bill Wakes explains this perfectly: “Writing a story card carries an implicit promise: I understand what I want well enough that I could write a test for it.” If you’re not sure on how you would test a story, this may indicate that the story isn’t clear enough.

How to use the INVEST framework to improve your user stories

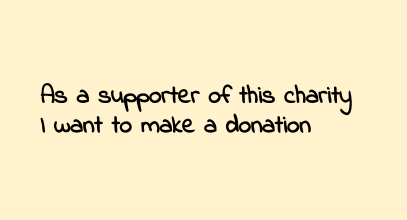

Looking at the above user story, let’s apply INVEST to it:

- Independent – No. This user story is too big to stand alone or be prioritised.

- Negotiable – Somewhat. But you could spend ages discussing it! This story doesn’t capture the essence of the need specifically enough to help you clearly understand it.

- Valuable – No. Whilst you can see how this could be valuable to the user, it’s not specific enough to pinpoint exactly what value you’re delivering.

- Estimable – No. You can’t estimate this easily because there are multiple potential parts to it. Are you talking about donating online or offline? Regularly or once? Talking to someone more technical would not necessarily help because it’s not focused enough on what you want to achieve with it.

- Small – No. This is a fairly large story! It needs to be broken down into smaller parts that are easier to understand and estimate.

- Testable – No. You can’t test it because the story is not specific enough about what it entails.

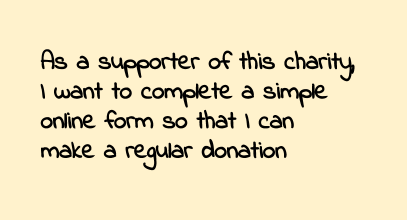

How could you rewrite this?

Now the revised user story is ticking the boxes of INVEST. It can be prioritised independently, it leaves enough room for discussion but it’s clear on the scope of the need that you must meet. You can understand the specific value that you are delivering to the user. It’s small enough that you can estimate it, and clear enough that you will know when it is done because if it works in the way that is described, you’re done!

If you’ve already written all your user stories, it may seem time consuming to have to review them. Not reviewing them will cost you more time!

If your stories don’t conform to the INVEST framework, you’re going to waste a lot of time working out where to start. Hours spent discussing the nitty gritty of the stories, or time wasted where designers or developers start working on stories that aren’t clear enough for them to deliver. By using INVEST, you will sift out the stories that are irrelevant and come out with a set of stories that you’re clear on, and that are actionable and measurable.

Getting started

Use the shorthand INVEST graphic above, so you’ve got a simple reminder of how to review your user stories.

If you’re reviewing user stories you’ve already written

The best way to do it is by gathering the same team that wrote the user stories. As a team work your way through each one. Depending on the skillset of your team, it’s likely they’ll each bring a different perspective to it. For example, a designer or developer will be better at estimating, whereas a researcher or user-facing team member will have a clearer picture of the core user need, and the value needed.

If you’re yet to write your user stories

As you write them, get the first draft of each out, then tweak until you’re happy they follow INVEST. Once you get the hang of it, you’ll find you start writing them the right way the first time. It’s best to write the stories as a team as it helps you to validate them as you go – collaboration brings a helpful mix of perspectives and experiences.

Now you have a set of clear, actionable, measurable user stories. The next step is to prioritise them, which will give you a list of work to start on right away.

In the next article, I’ll walk you through a simple exercise that will help you prioritise your user stories. We’ll look at ranking them by the value of what they bring to the user against the investment needed for you to deliver them.

Photo by Freddy Castro on Unsplash

Commissioned by Catalyst