Synthesising user research: how to do it

Awdur: Becky Colley;

Amser Darllen: 8 munud

Mae hwn yn adnodd agored. Mae croeso i chi ei gopïo a'i addasu. Darllenwch y telerau.

Os hoffech gymorth pellach gyda'ch her ddigidol, trefnwch sesiwn am ddim gyda DigiCymru

Listening to your users — to their needs, goals, and motivations — is interesting and invaluable. But listening is only the beginning.

Once you’ve undertaken user research you need to understand what it means. Synthesising it will help you do this.

What is synthesis?

Synthesis is a way of processing what you’ve learned and deciding what to do with it.

Depending on the type of research you’ve done there are different ways of going about this. These methods can be quick and high-level. Or more time-consuming but richer in insights.

For example, let’s imagine that you have a feedback survey running on your website. Users are asked to score their experience. Survey tools, like Hotjar and Maze, collate the responses so you can identify and analyse low scores. This is a fast and easy way of spotting things that don’t work as users expect them to.

Sometimes however, you need something more in-depth. Expanding on the example above, say you’ve noticed that a certain part of their website journey has a very low score. You don’t understand why so you test it via some user interviews then synthesise your notes. This shows you why things don’t work as users expect.

Why synthesise user research?

Synthesising user research will help you make data-driven decisions that will improve people’s experience of your services.

It will give you more confidence and help you prioritise improvements. You’ll know you’re solving real problems and making the most of opportunities.

What you’re learning will also provide you with evidence that justifies why you’re doing what you’re doing. And the impact it’s having.

Synthesising user interviews

You might want to start with our article about why you should do user interviews. User interviews help you to:

- fill gaps in your knowledge

- challenge your assumptions

- understand and empathise with your users

User interviews can include:

- questions about their life, behaviours, habits, expectations etc

- tasks e.g. testing a prototype, exploring solution sketches, testing an idea

They also take less time than you’d expect. It’s commonly agreed that conducting research with 6 participants is enough. This gives you just as many insights as speaking to many more.

It’s recommended that you speak to each participant for around 45 minutes. You can talk to all 6 people in a day. Or you can spread them over 2 days.

One person facilitates: asks questions, builds rapport, keeps the conversation on track. At least one other person makes a record of what’s happening. It’s best to keep note taker/s in another room. This stops the participant from feeling nervous or distracted.

If you’re interviewing someone over a video calling tool, like Zoom, your facilitator needs their camera turned on. This means they can engage better with the participant. You also need to be able to see the participant, so you can observe their body language and facial expressions. It’s best if those taking notes turn off their cameras once they’ve introduced themselves. Again, this avoids distractions.

Taking notes: real world

Let’s think about how we gather information first. Depending on how you capture notes, synthesis might take another day. Choosing the right capture method will save you time when synthesising.

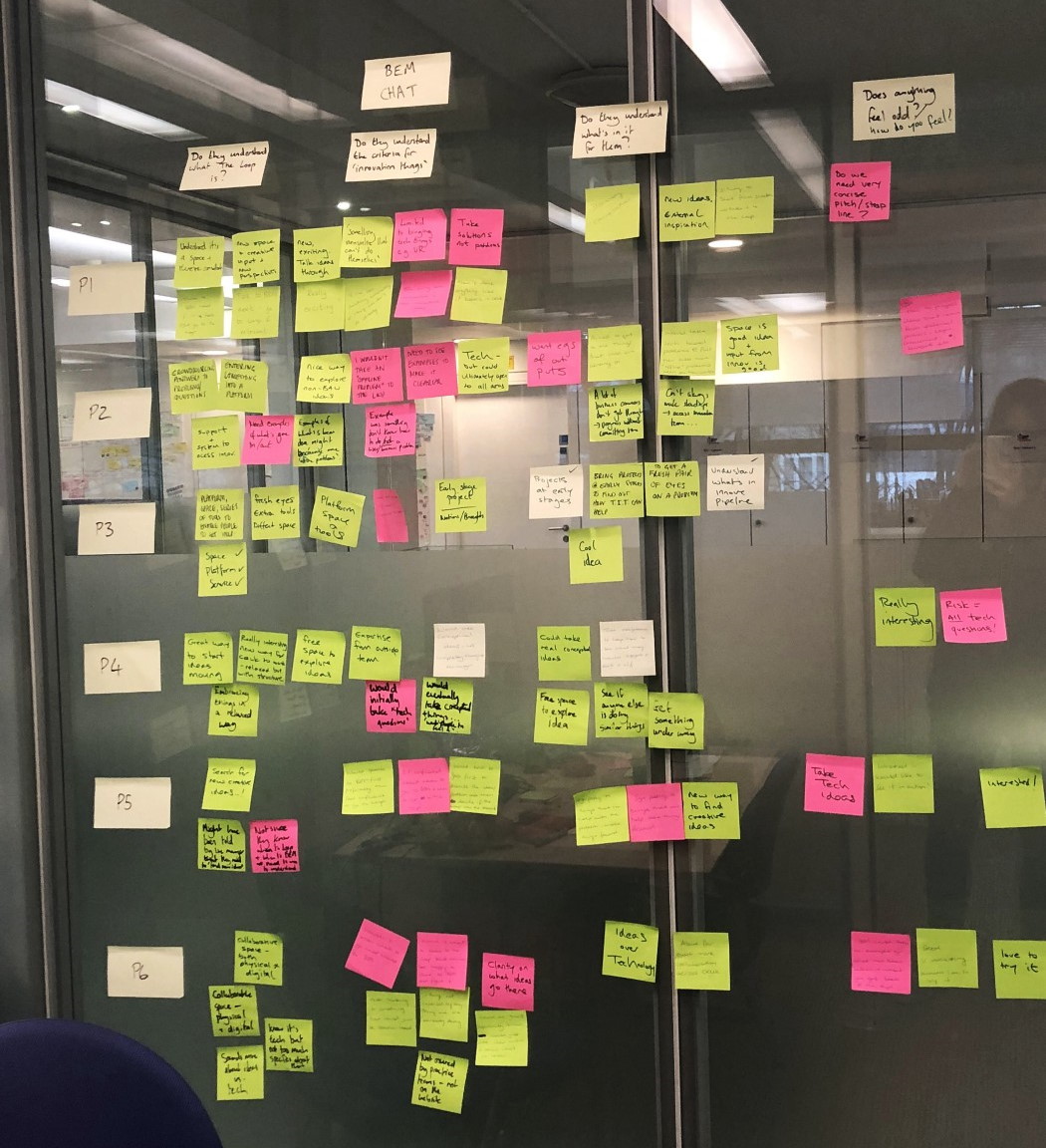

Note-taking usually involves writing interviewees’ thoughts, questions, and comments on sticky notes. Stick these where everyone else can see them and add their own observations.

Top tip: it helps to colour-code your stickies, e.g. a pink note means the user encountered a problem. This makes it much easier to spot issues at a glance later. For example, if there are lots of pink notes for the second interview task, you know that users struggled to use or understand this part of the design. Now you know to prioritise it when you iterate.

Another method is to use a shared spreadsheet, with a row per participant and a column per question. You can then take it in turns to capture as much as you can, from verbatim comments to tone of voice.

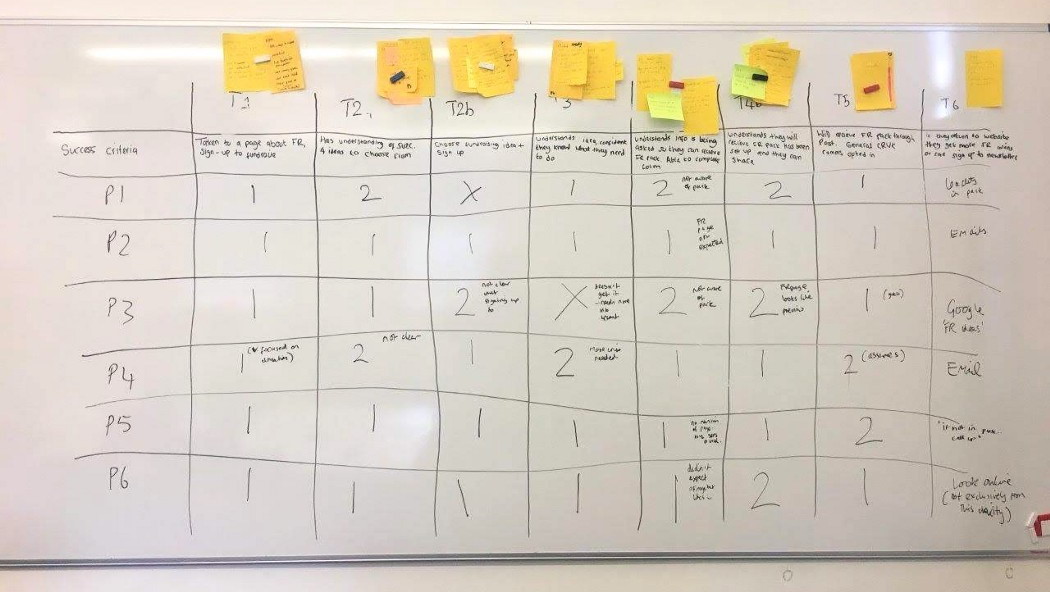

In the past I’ve also used whiteboards, drawing a table and ‘scoring’ participants. A 1 means they ‘passed’ a task easily, and a 3 means they struggled or even ‘failed’. Again, you can then quickly see where any glaring problems are.

Taking notes: online

In our increasingly online world, research is more often collated using a tool like Miro or Figma. You can use these just how you would with real-life sticky notes and whiteboards, and there are plenty of great free templates to get you started. Here’s a great Miro user research template, and here’s Catalyst’s free synthesis template.

Whichever method you use, it helps if note-takers jot down the times when participants do or say something interesting. It will save you time when referring back later.

Another option is recording audio notes. You might have a note-taker who has a visual impairment, or a motor difficulty, or who simply prefers to do it this way.

Whatever works for your team is fine.

Video recordings

Recording isn’t necessary, but really helps with note-taking. It also means that, later on, you can show others how your users feel and behave. It’s much more impactful to see an actual example, rather than hearing it from someone else.

If you’re using a professional user research lab, they’ll almost certainly record your sessions and share these with you afterwards.

If you’re doing it yourself, you can use any technology you have — even a phone. It can be easiest to use Microsoft Teams or Zoom, because they have built-in features to help you. Transcripts and captions make it easier to take notes, and they’re also more accessible and inclusive. For example if you’re sharing your research with d/Deaf people.

If you decide to record participants, be sure to get their permission. If you’re interviewing young people or people with learning disabilities, check with their parent/s, guardian/s, or carer/s. Be clear what you’ll use recordings for. Ask participants to sign something or give verbal consent during the recording.

Making sense of it all

No matter how you took notes, it’s a good idea to collate them using an online tool (like Figma, Miro, or Excel). You can more easily share this with others, to get their involvement, and even add video or audio clips so that everything is in one place.

Look for common patterns, such as low scores or particular-coloured sticky notes. Organise these in a way that makes sense to you. Group them together. Highlight a spreadsheet column in a bold colour. Create a graph to show the ups-and-downs of specific tasks.

Pull out specific quotes, and audio or video clips. What is it that makes them interesting? Does the user perfectly articulate the problem? Are they saying something positive, but their facial expression says something else?

This rich qualitative data is invaluable. It ‘fleshes out’ your quantitative research. It makes it more engaging when sharing with others. It can help you write “how might we” questions, by enabling you to see opportunities from a user’s perspective.

Remember: you’re not just trying to validate your ideas and assumptions. You want to truly learn what your users are struggling with so you can make improvements. You’re also looking for what you’re doing well, so you can keep doing it.

Sharing, collaborating, deciding

It’s fantastic if you can include your stakeholders at every point of this process. Depending on the size of your organisation this may not be possible, but what’s important is to involve others when you can.

Discussing your findings helps avoid bias. People with different lived experiences bring different perspectives. This includes those with different ethnic backgrounds, genders, and/or health conditions. Embrace all this!

Getting input from others can also help you to challenge assumptions. In my team, we have ‘playback’ meetings at the end of each discovery phase. Researchers share a research summary, play a video clip or two, and we all ask questions. It gives everyone a chance to feed in.

If you’re not part of a team, see if you can share with colleagues from another department. Or use your online support networks, like connections on Twitter or LinkedIn. Any extra viewpoints are useful.

Sharing your research ensures everyone is on the same page and you can get agreement about which insights should become what actions.

So, what next?

Start somewhere. It’s better to research and synthesise than not, even if it is a new activity for you.

Get more help from this Catalyst guide: How to find themes and insights from user interviews.

Or see how other organisations synthesise their results:

- Action for Children: Understanding and storing user research data using Mural and Trello

- Blood Cancer UK: look at Step 6 of Designing user-centred services using Miro, Figma and ChatGPT.

—

Main image by Jo Szczepanska on Unsplash

Wedi'i gomisiynu gan Catalyst